How to negotiate a logistics services contract

Negotiating a logistics services contract requires patience and attention to detail. As the shipper, you could be working with your logistics service provider for a long time, especially for warehouse services with long contract duration and difficult exit clauses.

When negotiating, be pragmatic and start with the question: “Are there any clauses that are non-negotiable?” This way, you can detect any show-stoppers early in the process. For the other clauses, reasonable, well-argued objections can usually be settled by give-and-take. A contract where one party takes all and refuses to give way has a weak basis and will usually lead to the other party walking away. Most contracts therefore are a result of balanced compromising.

Below are a number of standard contract clauses for warehousing logistics that require special attention. An open dialogue and understanding the impact of these clauses on both sides of the table will help you through your negotiations.

Clauses to watch for in logistics services contracts

- Scope of the agreement

- Exclusivity and/or minimum volumes

- Liability for direct and indirect damages

- KPIs and bonus-malus

- Terms and conditions

- Contract term and termination clause

- Price indexation

- Choice of law and venue

- Lien and retention rights

1. Scope of the agreement

The scope of a logistics agreement is a detailed process description of the services covered in the contract and the results these services are meant to achieve.

Why this matters: Often, services included in the scope of the contract are not clearly described. This leads to ambiguity in numerous following clauses. For example: A shipper might interpret ‘warehousing’ to include the entire range of services from arrival of the goods to the warehouse, up to the moment the goods leave the warehouse. In contrast, a logistics service provider might take ‘warehousing’ to refer to storage only. In this case, the contract does not clearly specify the services included in ‘warehousing’, and leaves clauses on KPIs and liability to be interpreted in various ways.

What to consider while negotiating: To avoid misunderstandings and ambiguities, clearly describe which services will be rendered under the agreement. Well-known examples of grey areas include loading, stowing and unloading under a contract of carriage. Always check whether the agreed Incoterm under the sales contract corresponds with the obligations of the carrier with regard to loading or unloading. Start the agreement with a preamble stating the overall objective. A preamble states facts and circumstances that are relevant to one or both of the parties, and helps in interpreting the clauses of the agreement in case of a dispute.

2. Exclusivity and/or minimum volumes

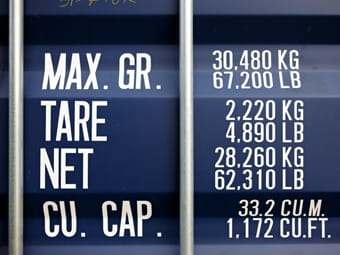

Exclusivity refers to the right of a logistics service provider to the total volume of a shipper. In logistics warehousing contracts, exclusivity and minimum volumes are usually expressed as a number of pallets in storage, as well as inbound and outbound movements. When distribution is included, it will also mention the number of shipments.

Why this matters: The single most important factor affecting logistics cost is volume. Logistics is by nature a volume-driven industry. As volumes are also the most important bargaining tool for shippers in order to obtain discounts, there is a short-term advantage in presenting the most favourable volume scenario. Still, substantial mismatches in volumes once the contract is started will in most cases re-open discussion on rates.

What to consider while negotiating: On the one hand, it is in many cases difficult to precisely predict volume developments. On the other hand, less volume for the logistics service provider means the contract is less profitable or even loss-making. Exclusivity makes shippers more vulnerable when logistics service providers underperform, with limited possibilities to react quickly to correct this. Cost/rates and volumes are key. Even if exclusivity and volumes are not explicitly mentioned in the contract, this does not necessarily mean that a shipper can freely change the nature and volume of the business as described in the tender documentation. Clearly describe the implications of substantial drops or increases in volumes and their effects on the negotiated tariffs.

3. Liability for direct and indirect damages

Direct and indirect damages are damages that occur due to an error on the part of the service provider or shipper, or due to another breach of one or more contract obligations by either party. It is natural that the shipper should want the service provider to accept liability for damage of any kind. At the same time, the shipper expects the service provider to offer competitive rates, yet these rates will have to include an insurance premium to cover the risk of any damage. Furthermore, service providers are careful not to leave themselves liable for potential substantial secondary damages such as indirect damages and/or consequential losses.

Why this matters: Shippers obviously want to make sure that logistics service providers are taking good care of their products. Penalties in case of damage are a way of ensuring that products are handled with care. However, it is less clear what damages occur as a result of missed or cancelled orders or flights, or delays in product delivery. Logically, the latter two examples of loss happen because the product was damaged or late through the direct or indirect fault of the logistics service provider. Inclusion of liability of the logistics service provider is complex. Often, it is more a matter of insuring against business risk, rather than simply ensuring that products are handled with care.

What to consider while negotiating: From a logistics service provider’s perspective, liability for damage to products is a way for the shipper to ensure that the service provider will do its utmost to handle products with care. From a shipper’s perspective, this liability for damage to products is sometimes considered full coverage for all possible damages in the supply chain. While it might be the natural tendency to allocate damage or loss to the party in physical possession of the goods, common practice in trade and commerce is to limit the amount or extent of logistics service providers’ liability.

For some types of contract, liability is limited by an industry standard or even by law (e.g. CMR). This is the case for contracts of carriage, where liability is commonly limited to a certain amount per kilogramme of gross weight, depending on the mode of transportation. Be aware, though, that this limitation only applies to the main obligations of the carrier. Other obligations undertaken by the logistics provider that are not subject to a contract of carriage nor an industry standard of liability can be arranged by contract.

If a 3PL accepts a higher liability for the goods, this affects the rates, as increased liability needs to be re-insured with an external insurance company. The logistics provider usually agrees to be liable for direct damages to the products up to a certain amount per kilogramme and/or incident in line with industry standards. Liability for damages exceeding this amount can only be covered by a separate insurance policy arranged either by the shipper or by the logistics provider on the shipper’s behalf. As it is virtually impossible to insure against indirect damages and/or consequential losses, logistics providers cannot accept liability for these.

4. KPIs and bonus-malus

Key performance indicators (KPIs) are metrics used to measure service quality. In a distribution contract, a typical KPI would be the percentage of on-time deliveries. Bonus-malus is a system that allows the shipper to withhold part of its payment for the services in case of underperformance, and it allows the 3PL to charge extra when it exceeds the agreed KPIs.

Why this matters: Quality usually comes at a cost. In particular, quality that exceeds the usual levels for logistics operations often mean extra handling, which incurs additional costs. Shippers obviously want the best level of service; 3PLs need to balance these expectations against costs.

What to consider while negotiating: KPIs are a useful tool to measure the carrier’s performance and to clearly outline the shipper’s expectations. Carefully consider which objectives need to be met in a service level agreement (SLA). If a SLA is meant to merely serve as a performance monitor, it would be sufficient to include it in a periodic performance review. However, if the SLA is meant to secure quality levels, then the consequences of failing to meet those levels should be clearly stated in the SLA. Such consequences usually include a contractual fine, and a maximum time to realise the required service improvements. If these improvements are not realised, this ultimately leads to cancellation of the agreement. On the opposite end, a bonus could be agreed in case of overperformance, thus giving the service provider a stimulus for improvement.

5. Terms and conditions

General terms and conditions are part of a logistics contract. They cover all areas that are not specific to one contract, but apply to the company as a whole. Matters that cover the performance of the logistics service provider on specific parts of the operations are not included in the terms and conditions.

Why this matters: Terms and conditions are helpful when drafting a contract because they contain many standard provisions, so that the contract itself remains lean and hence more transparent. However, terms and conditions are commonly drafted for the benefit of one party only. One-sided terms and conditions could distort any contractual balance reflecting the interests of both parties in the agreement.

What to consider while negotiating: A problem with terms and conditions is the so-called battle of the forms, with the purchasing party applying purchase terms and the performing party applying conflicting delivery terms. In practice, purchase terms and conditions are often drafted to be applied to a contract for the sale of goods or for the supply of services in general. These purchase conditions are usually less relevant for a logistics contract, especially contracts of carriage. To compound the problem, where international or cross-border services are involved, the solution as prescribed by law or jurisprudence varies per state. Therefore, it may be especially important to consider the choice of law (and court). In general, logistics terms and conditions that cover the interests of both parties are important to address all issues not directly stipulated in the contract. However, be cautious when including contractual terms and conditions that differ significantly from the general terms and conditions. For some modes of transport, a solution to both the battle of forms and to one-sided terms and conditions lies in sector-specific terms and conditions that are drafted by (representatives of) both purchasers and service providers.

6. Contract term and termination clause

The contract term is the duration of the logistics contract. The termination clause outlines the reasons or events during the contract period that would justify an early termination of the contract by the shipper.

Why this matters: For obvious reasons, logistics service providers benefit by maximising the duration of logistics contracts. The length depends on the effort and other investments involved in starting up and implementing the contract. For shippers, shorter contract durations enable more frequent re-negotiation of contract terms with the aim of reducing tariffs. Common negotiation points include the exact date that the contract is started, the period during which a prolonged contract needs to be agreed, and the notice period and prolongation period. Termination clauses are often points of contention because shippers regard them as an ‘escape route’ in case of severe problems. For logistics service providers, termination of contracts means large financial losses, because investments in setting up the operations cannot be recuperated.

What to consider while negotiating: Always agree on a contract term and/or a term of notice for cancellation. Stipulate clear and unambiguous termination clauses, a termination date and a notice term. If there is no such agreement, a reasonable term of notice would have to be established by court. The court’s interpretation of ‘reasonable’ does not always match the views of either party. When choosing the term of the contract, pay attention to whether the contract stipulates minimum order quantities (guaranteed volumes) and exclusivity. If so, the shipper must be sure that it can fulfil both these clauses for the entire contract term. Even if no guarantees on volumes are included in the contract, the carrier will still in many cases be entitled to a certain volume that was generated in the preceding period under the contract terms. In other words, even if no minimum order quantity was agreed to, the logistics service provider will often still be able to demand at least a ‘sustained’ order quantity.

Although contracts often cover both topics in the same clauses, bear in mind that there is an important difference between expiration of a contract and cancellation during the contract term. The latter typically follows grave shortcomings on the part of the logistics service provider. State in advance in the contract which shortcomings qualify as ‘grave’ and thus as grounds for cancellation. This is especially important in combination with exclusivity.

7. Price indexation

Price indexation is an annual exercise to adjust logistics tariffs by means of a price index in order to maintain the value of the contract after inflation and market-level price fluctuations.

Why this matters: The price index is the easy part, as indexation is calculated on a macro level by governmental institutions. An often-heard argument is that indexation should only apply to costs that are subject to inflation. Indexation is also sometimes used as bargaining leverage in discussions on continuous improvement. Indexation on the basis of ‘market price levels’ is the subject of even more debate. Given the long-term nature of most logistics contracts and the volatility in the market, logistics service providers often find it difficult to predict the cost of transport, for example, in two years’ time. Indexation of labour and rental costs on an annual basis is a common approach in long-term contracts.

What to consider while negotiating: Carefully consider which index to use for calculation. The chosen index must match the actual subject of the contract as closely as possible. Some components of the remuneration are usually indexed separately, notably fuel costs. If a separate fuel clause is included in the contract, ensure that it works both ways, i.e. that the purchaser is compensated when fuel costs decrease and that the carrier can apply a surcharge when fuel prices rise. Avoid double indexation by ensuring that the price indexation clause does not also include fuel. Sometimes shippers want to trade off price indexation against continuous improvement. However, it is best to keep continuous improvement separate from indexation and include it instead in a separate clause. For ‘market price level’ indexation, transport services that have little or no consolidation synergy (such as full truck loads, part loads or container transport) fluctuate heavily on demand. As these services are almost completely subcontracted, it is usually not possible to guarantee a fixed price for periods longer than one year, sometimes even less. Own-operated services or services with high volume consolidation synergies are less sensitive to sudden price-level fluctuations.

8. Choice of law and venue

This part of the logistics contract describes under which law any future disputes will be settled and the location of the court that will be the venue for any lawsuits.

Why this matters: When the shipper, the logistics service provider and the future logistics operation are all in the same country, this clause is hardly an issue. It gets more complicated when the shipper’s head office is in country A and the future logistics operation is in country B (sometimes even on another continent). In the case of large contracts, the location of the logistics service provider’s head office where its legal department resides adds complexity. Needless to say, all parties will prefer their own country’s law and a court as close to their home turf as possible.

What to consider while negotiating: The choice of law and venue can be decisive in the outcome of a case, even when uniform law from international treaties applies, such as in the European Union. Courts in different member states can arrive at diametrically opposing interpretations. One particular example where differences in interpretation have been noted is when determining whether damages were caused by the service provider’s willful misconduct. What qualifies as an act of willful misconduct is important, because it removes the carrier of its right to limited liability. The practical and logical approach is to use the law applicable to the country where the majority of the activities are being carried out.

9. Lien and retention rights

Lien and retention rights refer to the right of the logistics service provider to withhold the shipper’s goods, or even to sell these goods in case of unpaid invoices.

Why this matters: From a shipper’s perspective, not being to access one’s goods is worrying. Another concern is that this rule could be used as leverage during any disagreements about invoices. From a service provider’s viewpoint, these rights offer some degree of security that it will be paid for its services.

What to consider while negotiating: Problems with lien and retention rights are rarely directly related to the goods that are held by the logistics service provider. Instead, line and retention rights are typically exercised to enforce settlement of unpaid invoices for previous shipments or consignments. More importantly, retention rights are sometimes invoked not between shippers and service providers, but rather somewhere in the chain of subcontractors. It is sometimes difficult to prevent this from happening, but if goods represent a certain value, or if there is a particular interest in on-time delivery and corresponding contractual fines in the sales or supply contract, the shipper should carefully consider the risks accruing from lien and retention rights being invoked somewhere in the logistics chain. To avoid problems, choose a financially stable logistics service provider that orchestrates the various steps in the supply chain and centrally manages subcontractors.

All set to negotiate or re-negotiate your logistics services contract? Our experts are happy to share their advice and insights.

Any questions?

Our experts are ready to help. Get in touch and we'll find the solution you need.